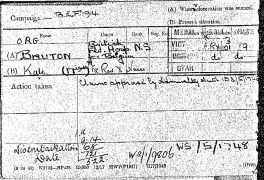

BRUTON, Kate Veronica

| Original items held by the Army Museum of Western Australia |

| Conflict | Anglo-Boer War, World War 1 |

|---|---|

| Service Arm | French Red Cross Australian Army Nursing Service |

| Unit | |

| Service No. | |

| Service Arm | Army |

| Date of Birth | 1 Nov 1873 |

| Birthplace | |

| Residence | |

| Date of Death | 23 Dec 1942 |

| Relatives | Father - Maurice Bruton |

During World War 1 Sister Bruton served with the British Field Hospital in Antwerp [September and October 1914] until it was forced to return to England. She worked at Hamsptead Hospital before joining the French Red Cross and returning to Europe. The British Committee of the French Red Cross were responsible for recruiting nurses to assist the French nurses.

Transcription of a letter Kate wrote to her father in December 1914. The letter was published in the Williamstown Advertiser newspaper on 26 Dec 1914 with the title "My Trip To Antwerp".

On September 5th I left Charing Cross for Folkestone with Miss Bryan's party for a field hospital for Belgium. A unit of 35 of us met at 12 10 p.m. and after nearly two hours waiting around the station where we were the centre of attraction to a crowd, with our purple cloaks, bonnets, and the lady farmers in khaki overcoats, riding breeches, top boots and helmets. There were only ten fully trained nurses, four lady doctors, three men doctors and three students. The rest of the crew consisted of four lady farmers, two wives of colonels, an Italian lady who was to act as interpreter, an American, who was bringing a motor car to use as an ambulance, a rich merchant with two cars and two chauffers and an English maiden lady with a car which she also was to use as an ambulance, A nurse rigged out in an army cape took upon herself the duties of chieftainess and ordered us around in a most insolent manner, spoke of her relations, Lord So-and-so, and was a queer party. I had about 20 Australian and New Zealand friends down seeing me off and I did not feel at all "alone in London.' The men, with their customary Australian generosity, provided me with some oranges and apples.

When we got to Folkestone the yacht which was to take us across to Ostend had not arrived, so we were left on the station for another couple of hours until some of the heads went to find accommodation. The only consolation we had whilst waiting was to hear the lady with the peerage relations tell a porter (for our benefit) that she had had a wire to go to Netley at once and join a troop ship so off she went and left us in peace.

We at last got to our various places, most of them schools where the pupils had holidays. The people were very kind and we stayed there until Monday, when the yacht still had not arrived. We left by mail steamer for Ostend and arrived safely there at midnight. Several cruisers put their searchlights on us and we hugged the coast for fear of mines.

We slept at the railway station on train cushions in the waiting room and next day sort of picnicked on the Quayside. Crowds of refugees were making for England as they thought the Germans were nearing Ostend. Next day some of our party went by train and the rest of us by motors. I was lucky enough to be in the first car and our driver had the password. We were challenged eighteen times along the road and once were sent a longer way round as the soldiers feared we might fall in with some Germans. However, we got to Antwerp safely and joined the others in a large schoolhouse lent by the Belgian Red Cross Society and fitted up with 200 beds. We crossed the river on a bridge made of barges lying side by side. Some being smaller than others made it look like a switch back railway.

For two days we unpacked our stores and tried to get things ship shape, but the head lady only thought of the look of things and brought oilcloth to cover the ink stained floor and pot plants for the halls ; mackintosh sheets for the beds and other useful things were not forgotten. Two hundred and fifty hot water bottles came from London and they were intended for a hospital of 40 beds. Pie dish frills and other ridiculous things revealed the fact that our organiser was not fitted to prepare a field hospital. No one seemed to have a say in the management but she, and as she was too excited and fussy to arrange anything, everything seemed in a state of muddle. We would be told breakfast was at 7.30 a m. and then someone else would come along to see why we were not at breakfast.

On Saturday morning patients began to arrive and before night we had 140 poor wounded Belgian soldiers. Some of them were very ill, those shot through the abdomen and one in the head dying soon after admission. The majority had shrapnel wounds in the legs, nasty big wounds they were, causing fracture of bone as well. We worked at high pressure and three of us (I one of them) were told off for night duty; we tried to get two hours rest once in the afternoon when there was a lull in admissions, but could not manage it with the noise. I have never met such a noisy lot of people-the doctors and students in heavy hoots and the lady farmers in their big boots seemed to tramp and the loud voices of most of our corps echoed all over the big rooms and galleries.

By 11 am next day we three tired and weary nurses crawled to bed in a large gymnasium room in a wing building where there were beds ready for more wounded should they arrive. We fervently hoped they would not arrive until we had a few hours sleep. We were very poorly fed. The lady farmers and colonels' wives, etc., who were going to do everything and anything in the kitchen department did not make progress. There was a supply of tinned tongues and Dutch cheeses, so we existed on them until a couple of weeks later a good cook was engaged, also some working women to clean up the place.

Two of the lady farmers had read up first aid books and considered themselves quite au fait in the nursing line; the other two helped in the dining room, the elder one being very good, the younger, only a girl, resented not being allowed on the field to bring in the wounded, so did not do much. They did not bring their horses from Ostend. What they thought they would do on horseback on the battlefield I'm sure I don't know. Their costumes might have suited farm life but hardly hospital wards. The English papers made great yarns on "The Spurred Ladies" who were going to "dash on to the battlefield and rescue the wounded." They vent out to Malines several days to help the Belgian Red Cross Society, but all we ever heard them say they did out there was peel potatoes, and we wondered why they did not stay with us and peel potatoes for our large crowd, seeing that at Malines there were no patients then.

All lights had to be out by 8 pm, and only hurricane lamps or candle were allowed, but as operations were often done at night we infringed the rule.

The lady doctors did not appear to be surgeons and the three male doctors sent for two others. One on stayed two days, the other was a London hospital man and keen only plating fractures, so he had plenty of practice there. He did six femurs and a couple of shoulders. How they were going to turn out was rather doubtful as the wounds were not healing very well when we got orders to quit and some of our patients were lost sight of.

On Saturday, October 3, we got orders to get all our patients that could be dressed, up and down stairs to go by train to Ostend, and then there was a rush Those who could hobble at all were helped down, others were carried and most of them went off by trams and ambulances. Three hours later we got fresh instructions to resume duty and take our patients back as Antwerp was safe. The British marines and big guns had arrived. Some of our patients returned and some from other hospitals returned to us, some of ours went elsewhere and some had gone to Ostend. We had a busy day trying to get 100 people back comfortably to bed, Sunday, we heard nothing fresh. Monday, we could hear guns and then some English soldiers were brought in— One told me that their guns were not big enough against the Germans and he feared his regiment would be wiped out. Tuesday, we were told if we wanted to go to England there was a boat out late that night and as I had been feeling knocked out and some nurses from another hospital could take my place, I left. Wednesday morning early the shells began to fall in Antwerp, and the patients were brought to the cellars, then on Thursday taken by cars to Ghent and Ostend and later to England. None of our party got hurt, although shells burst on houses on each side of the Hospital.

Antwerp was a fine city and such lovely homes. We were all billeted at various houses to sleep. We night nurses had most comfortable quarters, bedrooms as big as ballrooms and a bathroom on each floor; a maid to see to our wants as the mistress was at her Mother's.

One afternoon we were awakened by a cannon shot, and we jumped out of bed and ran to see what was wrong. We had been warned when we first came to Antwerp in the event of a cannon being heard we were to go to the cellar and keep away from the window. Of course this we didn't do. On looking out we saw the man and maid servant out on the road looking over our roof where it seems a "Taube" was flying. It had been seen by the forts and was fired on but got away. The next time one came we got a good view of it. It dropped a bomb on the water works and destroyed it, so that we were short of water for days. They had to pump water from the river into dry docks and condense it before we could get any laid on-all we could get was from some neighbor's well.